By Janet Naidu

Guyana Journal, March 2007

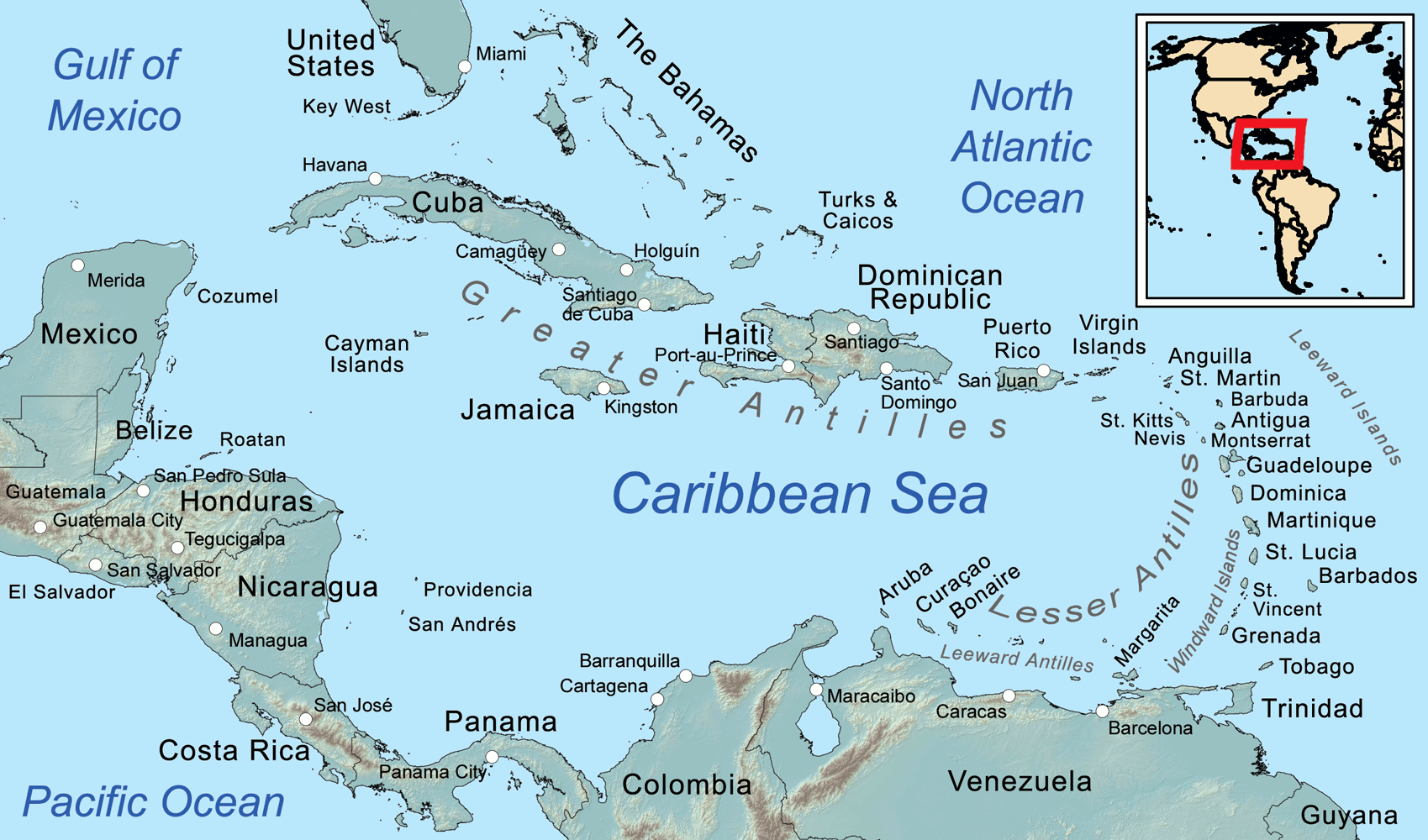

The emergence of Indian culture in the Caribbean region became evident as a result of Indians migrating from India primarily in the nineteenth century. Indians were transported as indentured laborers between 1838 and 1917 from India to then European colonies of British Guiana (Guyana), Trinidad, Suriname, Jamaica, Guadeloupe and other parts of the Caribbean. Of the nearly 400,000 Indians, Guyana and Trinidad received the majority, approximately 240,000 and 144,000 respectively.1 Some Indians secured their right to repatriation to India as stipulated in their labor contracts, while the majority of Indians settled in the Caribbean. What is important to note about their presence is that, with the arrival of a small percentage of Muslims and an even smaller percentage of Christians, the majority of Indians who arrived were Hindus.

The evolution of a new form of Hinduism in the Caribbean cannot be observed in isolation, but must be viewed against the experience of Indians as a whole under colonial oppression and their struggle for survival in a new environment. Given that approximately 90 percent of Indians were Hindus, it would not be difficult to make a case for Hindu cultural and religious traditions as being synonymous with Indian identity.2 Indians generally participate in cultural festivals such as “Phagwah” and “Diwali”, regardless of their religious beliefs. Like other colonized groups, while Indians socialized into the dominant European culture by adopting western language and other social practices, they also engaged in resistance in order to sustain their heritage, particularly their religious beliefs and practices.

This article examines the reconstruction of Hinduism in the Caribbean. It shows that Hinduism has survived in many ways as informed in India by religious texts such as the Vedas, the Bhagavad-Gita, the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Moreover, Hinduism has also experienced a transformation that reflects its exposure to the diversity of existing cultures and, therefore, a transculturation of Hindu religious beliefs and practices. The article examines unique religious observances that convey elements of Hinduism not only as a distinct religious identity, but also as a cross-cultural adaptation within a well-established Christian society. Thus, this reflects a process of adaptation by the Indians within Christian and Hindu ways of worship.

The persistence and transculturation of Hinduism in the Caribbean is most notable in specific aspects of religious and cultural realities such as: a) the reduction in practice of the traditional Hindu caste system, b) modes of worship and celebrations, c) the establishment of Hindu temples and d) the practice of Hindu ‘bamboo’ marriage. Since Indians were allowed to practice their religion in their new environment, to a large extent, Hinduism is very much alive in the Caribbean. This is observed mostly in Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname and, to a lesser extent, in countries such as Jamaica, Guadeloupe and other parts of the Caribbean where Indians migrated.3

While Hindu traditions are being implanted in the social milieu, at the same time, their social interactions with different cultures such as Africans, Chinese, Portuguese, Javanese, Amerindians and others paved the way for an evolution of new cultural constructions. For example, in a southern village in Trinidad, Hindus pray in a Catholic church. Similarly, in the former French colony of Guadeloupe, while Hindus have adapted to French culture, their religious practices survived within a dominant Christian space. Thus, it is evident that Hindus have found new ways to function within the scope of their new environment, which was influenced by former English, Dutch and French imperial rule. To a large extent, a two-way process of cultural embrace and exchange had shaped their adaptation. As a result, by virtue of cross cultural contact, identity has become an interesting phenomenon worthy of further examination as Hindus find themselves in the midst of established patterns.

Creolization

The term ‘creolization’ has had many interpretations and requires examination. With colonial occupation in the Americas, the term was first used to describe a “white” person of European origin who was born in the colonies. It also refers to their local food, music and clothing.4 Later ‘creolization’ became a dominant feature in the definition of a conquered people, particularly people of African origin who were referred to as “Creoles”. The loss of their ancestral language placed them in a different linguistic category as they adapted to European languages. It is therefore a stereotypical image associated with people based on their racial and linguistic realities. Furthermore, some people define the term to separate their identities and determine prejudicial preferences. As Salikoko Mufwene observes:

…in the Anglophone Caribbean the prevalent folk term for creole vernaculars is the French word patois (often represented as patwa in the relevant creolistic literature), a term which is not used for the same kind of vernacular in the Francophone Antilles….Calvet (1999) reports that white creoles in Louisiana will not refer to their French varieties as créole, although they are structurally similar to those spoken by black creoles. To be sure, they sometimes characterize those spoken by black creoles as créole, but they would rather use the terms cajun or patois in reference to their own varieties.5

The term ‘creole’ has recently been expanded again to address “the broad area of cultural contact and transformation” which characterizes the processes of globalization that was initiated by the colonial migrations of past centuries.6 Therefore, in examining the term “creolization” in the Caribbean region, many scholars are engaged in redefining Caribbean identity with respect to its evolution within the context of “colonial empires and national economic upheavals.”7 Furthermore, creolization implies a form of “indigenization whereby foreign elements could become native to the New World through creative mixings.”8Evidently, this is deeply rooted in colonial practices which recognize the significance of cultural importation as a dominant force of change.

The arrival of Indians brought a completely new culture where religion, language and social customs marked their unique identity. From the inception, they were considered different from the cultural groups already associated with western orientation. For example, in spite of their spiritual retention in such healing practices as Obeah and other rituals, Africans were forced to adapt to Christianity due to a system of religious indoctrination under European rule. Many restrictions were likewise placed upon Indians due to the atrocious conditions under which they lived and worked on the sugar plantations. Like the brutality of slavery that provoked African rebellions, the hardships that Indians endured also provoked resistance to oppression.9 To a large extent, the local inhabitants viewed Indians as outsiders, particularly because of their different cultural identity. At the same time, some Indians viewed themselves as outsiders, but mainly because of their contractual labor agreement that entailed a return trip to India. However, their settlement and adaptation paved the way for cultural association to be an important part of social change in the diversity of cultures. In her book, Callaloo Nation: Metaphors of Race and Religious Identity among South Asians in Trinidad, Aisha Khan examines Indians in Trinidad in the context of a “creolization” process. She argues that Indians can also be considered creole because “they are active creators of new cultural forms indigenous to the New World rather than being mere reproducers of ancestral cultural forms.”10 In this regard, their practices are unique to their exposure and settlement in a society already developed by African spiritualism and European religiosity.

Today, “creolization” appears in writings synonymous with such terms as “hybridity” and “syncretism” to reflect the mixtures among different peoples as migration occurs. However, this broad anthropological term is appropriately described as “any coming together of diverse cultural traits or elements…to form new traits or elements.”11

The mixing of languages or other cultural traditions may be a reflection of creolization, for cultural adaptation and cross-cultural experience. However, the term “transculturation” seems to be more applicable to the reconstruction and transformation of Hinduism in the Caribbean. In spite of the dominant European environment, Hindus began to observe their religious faith upon their arrival. They found different ways to worship, even if it meant in the privacy of their homes or in the Christian church. Thus, in order to address Hindu practice and its reconstruction in the Caribbean, one must address the meaning of “transculturation.”

Transculturation

The term transculturation was coined in 1947 by sociologist Fernando Oritz (1881-1969) to describe the process by which a conquered people choose what aspects of the dominant culture they will assume and, through this process, they actively decide in the formation of their cultural identity.12 Ortiz’s theory of “transculturation,” demonstrates that uprooted peoples, mainly of European and African origins, primarily engaged in a shared experience in the evolution of Cuban culture.13 Tansculturation recognizes the power of the subordinate culture to create its own version of the dominant culture where the phenomenon of “merging and converging cultures” reflects the people’s natural tendency to resolve conflicts over time, rather than to exacerbate them.14 While Ortiz presents the converging of the predominantly European and African cultures in his transculturation theory and reflection of Cuban identity, his theory is applicable to others, including the Chinese of Cuba.15 As Frank Sherer notes, in constructing Cuban identity, further examination should be given to what “Chineseness” means in the construction of Cubanity or “Cubanness”.16 Ortiz’s theory may also be applied to other societies such as Indians in the Caribbean. In this case, Hinduism in the Caribbean may arguably be seen in the context of “transculturation” rather than “creolization”.

As an uprooted people from India, Indians were placed in a remote environment which was already developed with Native Peoples, African and European cultures and Christian orientation. Further, Indians were not only subject to linguistic challenges such as English, Dutch and French, but they also entered a predominantly Christian environment and European mode of expression. Nevertheless, because of their indentured contracts which entailed their return to India, plantation owners allowed Hindus to practice their religion on the sugar estates. This way, Hindus were able to develop new ways to introduce their religion in a new environment. In this context, the concept of “transculturation” shows that the introduction of Hinduism in the existing culture has caused the evolution of certain religious practices to be observed differently than they were observed in India.

Unlike Mary Pratt’s notion of transculturation in the study of travel writings by Europeans, Fernando Ortiz’s theory of transculturation clearly takes the significance of the native people into consideration. Pratt uncovers European writings that focus on the ideologies of the European conqueror’s views of native peoples. She claims that such writings reveal more of European society as “symptoms of imperial ideologies” and how such ideologies are “received and appropriated by groups on the periphery – and how transculturation from the colonies to the metropolis takes place.”17 On the other hand, Ortiz shows how native peoples introduce their cultural realities to affect social changes in a society. Moreover, he brings to light the merging of cultural groups and formation of a new people as depicted in the Cubanness of Cubans.

Taking Ortiz’s approach, there is no question that the evolution of Hinduism in the Caribbean demands an examination of cultural formations through the eyes of the conquered people. By examining their cultural and religious identity in context of their displacement and social upheavals, their experience and association can then be seen from the perspective of their empowerment while under indentureship. One of the significant forms of transculturation is the evolution of the new language, “Sarnami”, that has been developed in Suriname as a result of people coming together with their different languages that converge to form a new indigenous language. It may be seen as a reflection of people’s natural tendency to come together in harmony rather than be in conflict with their differences.

In the process of transculturation, while Indians participate in events such as “Mashramani” in Guyana and “Carnival” in Trinidad, some Indians fear that there is some degree of erosion of their cultural identity. Further, due to such fear, they may be unwilling to embrace the social change in a pluralistic environment where the mixing of different cultural groups is inevitable for social harmony. While Aisha Kahn calls it a “Callaloo Nation” in Trinidad, Viranjini Munasinghe shows the complexities of Indian identity in the Caribbean and indicates that Indians take exception to the “Callaloo” metaphor, arguing that it is “boiled down to an indistinguishable mush….”18 She provides an insight into the dynamics surrounding the force of transculturation and the efforts by Indians to preserve their identity:

…the original ingredients lose their respective identities and blend into one homogeneous taste. They disapproved of this metaphor because it represented an extreme level of blending or “mixture.” Instead they opted for the metaphor of the “tossed salad” – an image which also signified diversity but one where, unlike the callaloo, each diverse ingredient maintained its originally distinct and unique identity.

Indo-Trinidadians who are intent on preserving what they believe to be their unique and distinct “Indian” identity are against a “callaloo” nation because of the extent of biological and cultural mixing signified by this metaphor.19

While Hinduism is retained in the Caribbean, no matter how similar certain observances may be similar to their ancestral practices, because of migration and interaction with other cultures, Hinduism has not only survived but has also become different in the Caribbean.

The Hindu Caste System

The traditional hierarchical Hindu caste system is considered a hereditary class, having its origin in Vedic times, and based on responsibilities, with its main categories as Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas and Shudras as well as the ‘outcastes’ who are categorized as ‘untouchables’ or ‘dalit’.20 Although the preservation of caste “was an essential element of Hinduism and those who deviated could face severe social ostracism”,21 it gradually became less significant once Hindus left the shores of India and crossed the kala pani,22 as they would be considered contaminated and as a result, would lose their caste status. For this reason presumably, very few Brahmins were recruited.23 Mainly from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar with a minority from Tamil Nadu, many Indians of varying castes were shipped to the Caribbean. In 1883, about one-third of the immigrants who arrived were ‘untouchables’ or ‘dalits’ who were discriminated against as outcastes of Hindu society.24 Since varying castes commingled in the same ship, they had to eat the same food and share the same space. The psychic torture associated with the colonizer’s exploitation forced them to come together and share their experiences and sufferings in spite of their different castes or languages such as Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Urdu.

Once Indians were on the ship together, they became jahajis (shipmates) and caste became less important. They started to develop a unity under the Indentureship system. Although Indentureship provided a sense of freedom from the caste system, many Hindus practiced the caste system during their indentureship period as was evident in parental arrangement of their children’s marriages within the same caste. However, while caste identification tended to be preserved among Indian indentured laborers who came initially, it became inconsequential in social interactions except in the case of the few Brahmins who were required to perform religious ceremonies.

In many instances, due to inter-marriages and social interactions, the caste system (as was practiced in India) was not as prominent even though some people still pejoratively referred to others as “high” or “low” caste to distinguish their caste identity. Nonetheless, within the Hindu community, because Brahmins were instrumental in the establishment of Hindu religion, their higher caste status remained as an important and pivotal feature of social life, particularly because of their religious orientation. In this way, Hindus developed a shared support base as one people entering another land. However, they not only identified with one another as ‘Indians’ or ‘Hindus’, but they have also come into contact with peoples from different cultures who had already experienced oppression under European domination. In examining Hinduism as a new religion in the region, one cannot ignore the system of oppression that Hindus faced, particularly during the Indentureship and post-Indentureship periods. In spite of the poor working conditions and ill treatment on sugar plantations, they found ways to maintain their Hindu religious practices.

The fact that the majority of Hindus who migrated to the Caribbean were primarily from the rural areas of India and were uneducated, they relied on their memory for the continuity of their religious practices while working under the harsh conditions on sugar plantations. Further, due to many being duped into leaving India, the majority could not bring their religious texts, sacred items or other necessities for ritual observances. However, the sacred teachings of the Bhagawad Gita and other religious texts such as the Ramayana and Upanishads had been etched in their memory. In addition, the Brahmins helped them to sustain their religious practice. Many of the stories and epic poems were/are played out in such celebrations and observances as Ram Leela, Diwali and Phagwah. Even with the absence of Hindu temples initially, they had access to a religious space to keep their faith.

The emergence of Presbyterian churches in Trinidad has paved a strong road for Hindus to worship in a Christian sphere of influence. Also, the Arya Samaj and Maha Sabhas have played important roles in the preservation of Hinduism in Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname. Because Indians were allowed to practice some parts of their culture, India became a historical reference for continuity and change of Caribbean Indians. In the process also, Hindus have created their own version of worship as can be observed in their worship of the Virgin Mary as a representation of the Hindu Deity Kali Mai.

Worship of the Hindu Deity Kali Mai

While Hindus worship different deities such as Rama, Sita, Radha and Krishna who are central in the religious texts of the Ramayana and Bhagavad-Gita, they also worship Mother Kali. However, the worship of Mother Kali is a common phenomenon among a minority of Hindus who migrated from Madras (now Tamil Nadu). It is not a “Brahmanic” upper caste worship, but a lower caste one where animal sacrifices are made to the deity.25 Mostly Tamil-speaking Hindus worship Mother Kali in places such as Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname. Also, in spite of the small number of laborers who went to the former French colony of Guadeloupe, Indians held on to their faith and soon started to worship Mother Kali, including the Deity called “Mariaman”. Their adaptation results in some Hindus observing both Catholic and Hindu faiths. With the compulsory Catholic Christian religious indoctrination, some Hindus had to adapt to new ways of worship. Interestingly, they do not perform any pujas during the Christian observance of “Lent”. This is part of the “religious syncretism” which is due to their historical and social conformities.26 While they attended the Catholic Church, Hinduism became a part-time practice, as their temples were isolated in the country. According to Oliver Moonsammy Indains were “catholic in the society, but Hindus in their heart and at home.”27

One of the important aspects of Hinduism is that some Africans (in Guadeloupe) have been drawn to the Black Deity as devotees. The worship of Mother Kali has attracted other ethnicities because of the Deity’s presumed power to heal the sick. Africans in particular have identified with the healing aspect of this form of worship. This is mostly likely due to the fact that since Africans had already brought their own spiritual healing practice from Africa, such as Obeah, they were drawn to the similar form of ritual that Mother Kali provided. This similarity of spiritual healing is a natural association among Indians and Africans in the worship of the Black Mother Kali. It is interesting to note that the more Africans worship this Hindu deity, the more cross-cultural connection occurs between the Indian and African ethnicities.

Guyana is known to have established many Madras Temples in the Berbice region, particularly in the Albion village where Hindus worship Mother Kali.28 The majority of Hindus who migrated from India began to establish Ashrams or Temples where they worshipped other Deities, including Mother Durga. On the other hand, the minority of Tamil-speaking Hindus established Madras Temples, often called Kali Temples, specifically established to include their worship of Kali Mai. There was a perception that “Madrasees” are lower caste and because of “Brahmanic” upper caste prejudices, many Madrasees became easier targets for Christian conversion. In Guyana, many Tamils became Lutherans. However, on the whole, while the worship of Kali Mai is perceived as a lower caste tradition, the Black Mother has not only afforded a form of freedom and healing from oppression, but also served to empower indentured laborers while they endured great suffering under harsh living and working conditions. What is strikingly different from Indians who first arrived in the Caribbean is the transformation their descendents have been making in the creation of their own version of religious practice. For example, in Guyana, some pujaris only perform vegetable sacrifices to Kali Mai and the burning of offerings which “propitiates the divinity”.29 Other changes took place in ways of worship.

La Divina Pastora

An interesting development emerged in Trinidad where Hindus began as early as the 1870s to worship the Catholic Virgin Mary as Mother Kali. The Catholic La Divina Pastora, meaning “The Divine Shepherdess” became popular among Indians who believe that the Saint was very much their own. It was observed in October, 1917 on the feast day of the Saint, estate workers would take a three-day leave to worship Mother Kali in the form of the Virgin Mary and attend the feast, in spite of the objections of the estate owners. Although the estate owners brought a statue of the Divine Shepherdess to Laventille Hill, christened Siparia Hill, it was later moved to La Pastora.30

South Indian Hindus in Siparia, being a minority, struggled to retain their worship of Mother Kali in similar way that the North Indian Hindus worship such deities as Shiva, Vishnu and Krishna.

A new phenomenon developed at the Roman Catholic shrine of La Divina Pastora where Good Friday has been reserved for Hindus to worship their Mother Kali in the form of the dark-skinned wooden statue of the Virgin Mary. To Indians in Trinidad, the Virgin Mary is “Siparia Mai”, because to them, Kali Mai traveled with them across the kala pani and took on another form in the Virgin Mary.31 This is an interesting form of transculturation where Hindu religious practice takes on the adaptation of a Christian holy representation. Unlike the Presbyterian Church that assisted in the indoctrination of Indians to Christianity, some Hindus chose the Roman Catholic Church at Siparia as their place of worship. It is believed that this phenomenon is the only one in the world and is unknown by Hindu scholars in India.

Hindu Temples

During the indentureship and post-indentureship periods, Indians turned to India for cultural and religious knowledge which helped them to maintain their identity with the Indian sub-continent. This is evidenced in the number of Hindi films that provided awareness of Indian social customs. In addition, commercial retail stores provided Indian items for their social needs such as the performance of rituals at weddings, pujas, jhandis and religious ceremonies. However, with the integration into the Caribbean westernized culture, Indians no longer relied upon India for the formation and continuity of their religious and cultural practices. Thus, at the end of indentureship in 1917, in Guyana for example, there were 43 temples and 46 mosques.

The Sanatan Dharma Maha Sabha served as the backbone behind the promotion and retention of Hinduism, where they not only trained Pandits to deliver religious services at jhandis, pujas in their homes and at temples, but they were also trained to conduct marriage ceremonies and to serve the needs of the Hindu community based on their cultural traditions and religious values. Further, as a society, they also encouraged the study of Hindi and Sanskrit. The reconstruction of Hinduism is seen in the emergence of temples in highly Hindu populated places in the Caribbean such as Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname. Throughout the Caribbean where Hindus live and worship, Hinduism continues to experience a revival, including in places such as Guadeloupe and Martinique through temple construction and other religious observances. In Barbados where Indians have migrated from places like Guyana and Trinidad, Hindus have not only erected a temple as recently as 1995, but also celebrated “Diwali” at a Catholic School.34

Jhandis

The spirit of Hinduism is seen in the symbol of the “Jhandi” flag, typically in red, which represents the God Hanuman, a devotee of Sri Ram in the epic tale of Ramayana. The transportation of this religious observance from India is different in that the flag was usually placed near a temple. However, without the physical temple structure, Hindus found a place in the corner of their yard to represent a temple. Some would partition an area in their yard and build a makeshift temple with flowers planted and a stone laid to conduct their prayer. Later, they built a small one-person temple to pray. The jhandi flag would be placed outside in this spot. Prior to the building of temples to serve as a public place of worship, Hindus started by worshipping in their homes in the form of a simple “puja” with fresh flowers, burning of incense and the placement of a picture of their deity. Afterwards, the ritual culminates in the symbol of the jhandi flag placed outside their homes, typically in their yards.

Indians brought a unique culture to the Caribbean, that represented a diversity of practices, but the Bhojpuri tradition became the dominant feature.35 This tradition influenced many cultural activities in Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname. Since these were all new to Africans and other cultural groups, Indians were seen as foreign and strange. Over time, Africans and Indians, the two main groups in Guyana and Trinidad, found a common experience of oppression under the colonial rulers and developed neighborly relations, as they co-existed in their own cultural identities. However, while some Africans participate in Indian celebrations such as Phagwah and would delight at the celebration of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, the religious faith remains uniquely an Indian Hindu tradition. While people may be intrigued by the flags, they are even more delighted with construction of tents in the yard during bamboo weddings, the music and food, which form part of a grand celebration. Hindus usually invite their neighbors to participate in the celebration of their children’s marriage.

Hindu Marriage

Transculturation is seen in Ortiz’s African and European contact; it can also be seen between African and Indian contact in some shared similarities such as food and music. The movement of Hinduism from India to the Caribbean can be seen not only in the celebration of social customs such as bamboo weddings and playing of Indian music that can be heard from one village to another, but also in the emergence of an ideology that can have the potential for isolating a people from the rest of the society. While their arrival in the Caribbean brings them into contact with other peoples, predominantly African, with a minority of European and Amerindian groups, Hindus face the challenge of retaining their religious faith due to an ongoing mixing of their cultural identity.

Many Hindu weddings have taken on a dual Indian/Western celebration. They have retained their traditional Hindu marriage ceremony and at the same time, they have adapted to a European tradition of celebration. For example, they conduct an elaborate Hindus ceremony with Indian ‘Nagara’ music and later, they also celebrate in a Western style wedding reception with western music, dances and wedding cake. The couple not only solemnize their wedding under the Hindu bamboo maro, where the bride and groom wear traditional Indian attire such as the sari and kurta, but they also celebrate their marriage in the Western tradition where the bride and groom wear western style clothes such as a white gown and a dark three-piece suit. African friends and neighbors are often guests at such celebrations and partake in dancing to Indian music such as Chutney and “Nagara”.

Conclusion

In examining the reconstruction of Hinduism in the Caribbean, there is a great degree of solidarity among Indians in the Caribbean, regardless of their Hindu, Muslim or Christian orientations. This is based on their cultural perspectives and their participation in the diverse cultural and festive activities. Similarly, African Caribbean people also participate in the festive occasions and domestic celebrations such as phagwah, diwali, weddings and parties. However, as Hindus continue to observe religious traditions rooted in their religious texts, they provide an awareness of Hindu customs for an independent identity.

Although Indian Muslims and African Muslims partake in a shared religious observance, Hinduism remains, to a large extent, an Indian exclusive form of gathering. Thus, it limits the trend of mixing that transculturation provides. Fernando Ortiz’s theory of a transformed society reveals that it is the culmination of different cultures that make up an evolving society as noted in Cuban identity. Is the tension between Africans and Indians, particularly in Guyana and Trinidad, an inherited legacy of colonial ‘divide-and-rule’ instigation, or is it a struggle for political power? Does religious orientation exacerbate the struggle for unity? While strained relations between Muslims and Hindus exist in countries such as India and Pakistan, the Caribbean is not noted for such hostility. However, if Hinduism in the Caribbean appears to be synonymous with “Indianness”, Muslim and Christian Indians will most likely feel excluded from the Indian identity. Furthermore, is there an effort to establish a distinct Hindu society that may consequently alienate other ethnic groups? Will it take a few more generations for Hindus and other groups to enter a shared space where cultural integration becomes a greater recognition in the national identity? Some of these questions are posed to open more discussion and examination of cross-cultural and religious identity, association and appreciation in the Caribbean. In particular, it is evident that further discourse is needed to unravel the relations between the main ethnic groups and to expand ways to promote their peaceful co-existence. Undoubtedly, this could only foster respect for cultural and religious diversity as well as a movement towards an inclusive society. Moreover, if descendants of Hindus are becoming less involved in the religious practice, perhaps Ortiz’s theory of transculturation will be a point for further exploration.

References

1 Brian Ally. “East Indian Indentureship.”

2 Patricia Mohammed. “Hinduism – Gender Relations”.

3 Latchman P. Kissoon. “Hindus in Barbados”.

4 Professor Frederick I., Case New College, University of Toronto, personal communication.

5 Salikoko Mufwene. “Creolization is a Social, not a Structural Process”.

http://humanities.uchicago.edu

6 http://www.rodopi.nl/frameset/bbs/rightside.asp?BookId=MATATU+27-28&type=browse

7 Kathleen M. Balutansky and Marie-Agnes Sourieau (eds.). http://www.upf.com/Spring1998/balutansky.html

8 Viranjini Munasinghe. “The Indian Community in Trinidad: An Interview with Viranjini Munasinghe”.

9 Frank Birbalsingh. Indo-Caribbean Resistance. p. viii

10 Ibid.

11 http://www.cajunculture.com/Other/creolization.htm

12 http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/encyclopedia/T/Tr/Transculturation.htm

13 Rafael Flores. “The Cuban Son: In Disguise.” UMass Amherst.

http://www.fivecolleges.edu/sites/cisa/symp2001/

14 http://encyclopedia.laborlawtalk.com/transcultural

15 Frank F. Sherer. “Chinese Shadows: Fernando Ortiz and Jose Marti on Cubanity and Chineseness”, p. 1

16 Ibid. p. 11

17 Mary Louise Pratt. Imperial Eyes. Travel Writing and Transculturation (Introduction).

18 Viranjini Munasinghe. “The Indian Community in Trinidad: An Interview with Viranjini Munasinghe”.

19 Ibid.

20 www.hindubooks.org, p. 1

21 Basdeo Mangru. Indenture and Abolition, p. 52

22 Kala pani means ‘dark water’ and once Hindus leave the shores of India across this dark water, they are considered impure.

23 Patricia Mohammed. “Hinduism – Gender Relations”.

24 Moses Seenarine. “Recasting Indian women in colonial Guyana: gender, labour and caste in the lives of indentured and free laborers”.

25 Oliver Mounsamy. “Hinduism in Guadeloupe.”

26 Oliver Mounsamy. “Hinduism in Guadeloupe.”

27 Ibid.

28 Nagamootoo, Moses. Hendree’s Cure

29 Frederick Ivor Case, “The Intersemiotics of Obeah and Kali Mail in Guyana”.

30 Angela Piddock quoted by Kumar Mahabir, “Hinduism in Trinidad”.

31 McNeal, Keith. “BWIA Caribbean Beat”, March/April 2002. pp. 75-79

32 Marion Ocallaghan, quoted by Kumar Mahabir. “Hinduism in Trinidad”.

33 Peter Ruhomon. p. 259

34 Latchman P. Kissoon. “Hindus in Barbados”.

35 Basdeo Mangru. “Indenture and Abolition”.

Further Reading

Ally, Brian. “East Indian Indentureship”. 2002. http://www.cariwave.com/East_Indian_Indentureship.htm

Balutansky, Kathleen M. and Marie-Agnes Sourieau (eds.). “Caribbean Creolization: Reflections on the Cultural Dynamics of Language, Literature, and Identity”. http://www.upf.com/Spring1998/balutansky.html

Baumann, Martin. “Becoming a Colour of the Rainbow: Indian Hindus in Trinidad Analysed along a Phase Model of Diaspora.” 18th Congress of the International Association for the History of Religions. Durban, 2000.

http://www-user.uni-bremen.de/~mbaumann/lectures/durb-dia.htm

Birbalsingh, Frank.(Ed). Indo-Caribbean Resistance. Toronto: TSAR Publications, 1993.

Case, Frederick Ivor. “The Intersemiotics of Obeah and Kali Mai in Guyana”. Nation Dance. Patrick Taylor (ed.). Bloomington: Indianna University Press, 2000.

Flores, Rafael. “The Cuban Son: In Disguise.” UMass Amherst.

http://www.fivecolleges.edu/sites/cisa/symp2001/

Khan, Aisha. Callaloo Nation: Metaphors of Race and Religious Identity among South Asians in Trinidad, London: Duke University Press, 2004.

Mangru, Basdeo. Indenture and Abolition: Sacrifice and Survival on the Guyanese Plantation. TSAR. Toronto, 1993.

McNeal, Keith. BWIA Caribbean Beat. March/April 2002. pp. 75-79

Mufwene, Salikoko. “Creolization is a Social, not a Structural Process”.

http://humanities.uchicago.edu

Munasinghe, Viranjini. “The Indian Community in Trinidad: An Interview with Viranjini Munasinghe” based on her book Callaloo or Tossed Salad?: East Indians and the Cultural Politics of Identity in Trinidad. New York: Cornell University Press, 2001. http://www.asiasource.org/society/callaloo.cfm

Nagamootoo, Moses. Hendree’s Cure. Leeds: Peepal Tree Press, 2000.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London and New York: Routledge, 1992.

Ruhoman, Peter. History of the East Indians of British Guyana 1838-1938. Government House, Georgetown, Demerara, British Guiana, October 1946. Georgetown: Reprinted by the East Indian 150th Anniversary Committee, 1998.

Seenarine, Moses. “Recasting Indian women in colonial Guyana: gender, labour and caste in the lives of indentured and free laborers”.

http://www.saxakali.com/Saxakali-Publications/recastgwa.htm. 1996.

Sherer, Frank F. “Chinese Shadows: Fernando Ortiz and Jose Marti on Cubanity and Chineseness” http://www.yorku.ca/cerlac/chinese-shadows.pdf

http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/encyclopedia/T/Tr/Transculturation.htm

http://www.hinduism-today.com/archives/1995/8/1995-8-02.shtml

http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=11376851790923

Copyright © Guyana Journal. All rights reserved