The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art here at Northwestern University is hosting “Collecting Paradise: Buddhist Art of Kashmir and Its Legacies” through April 19. The exhibition features 44 objects: manuscripts, paintings and sculptures in ivory, metal and wood, dating from the seventh to 17th centuries. Free to the public, the official inauguration Jan. 17 includes an overview by its curator and art historian Robert Linrothe.

This most ambitious exhibition in Block’s history presents and interprets the consecrated religious artefact in its original social context, but also questions how its significance might be transformed by the very fact of being collected, transported far across space and time to be re-housed in a modern museum.

“As part of our new global initiative, this exhibition brings together works of Asian art that are true masterpieces — among the most important of their kind in the U.S.,” said Block’s Director Lisa Corrin. “Professor Linrothe is one of the few experts in the art of this region teaching in the U.S. today. He has spent decades traveling to remote locations to study historic sites and form relationships with local experts. This direct experience of the art of Kashmir and the Western Himalayas ‘in situ’ has contributed to his innovative and thought-provoking thesis on the migration of culture,” Corrin added.

A companion exhibition, “Collecting Culture: Himalaya through the Lens,” that runs through April 12, further examines the impact of centuries of collecting in the region. It looks critically at U.S. and European engagement in the Himalayas beginning in the mid-19th century, through lenses including photography, cartography, natural science and ethnography. It likewise reflects on the ways Westerners have perceived, defined and acquired the Himalayas, The expeditions of four collectors from late 1920s through 1940s are presented, and 11 of their acquisitions are included. This enables museum visitors to consider the motivations and actions of these individuals, as well as contemplate the impact of transferring consecrated objects from religious shrines to museums, where they are presented for their aesthetic value.

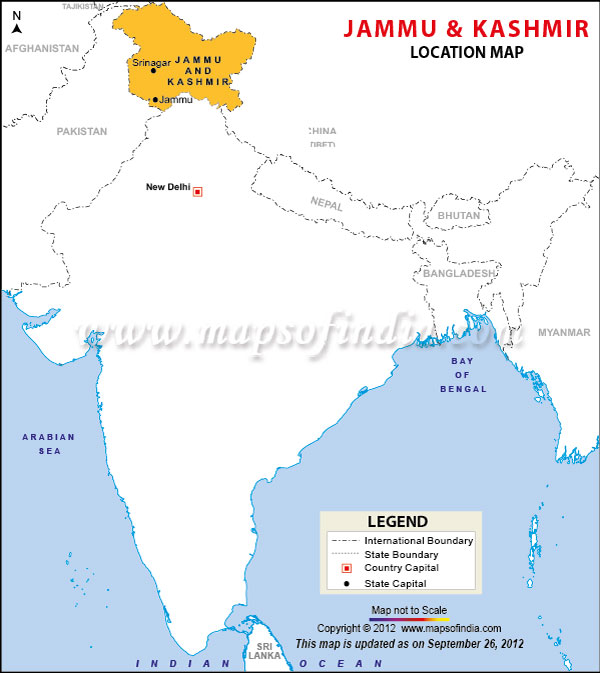

From the seventh to 11th centuries, Kashmir — a lush valley connected to the Silk Road — was a wealthy center of transcultural trade, culture and religion. Beginning in the 10th century, Buddhists in the Western Himalayas traveled to Kashmir to acquire, preserve and emulate its sophisticated art.

Kashmiri artists also accepted invitations to travel to the Western Himalayas during this period to work with and teach local artists. The distinctive workmanship of the “Kashmiri style” became integrated into the identity of Tibetan Buddhism in this period and experienced a revival in the Western Himalayas in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Centuries later, beginning in the 1900s, artworks from Kashmir and the Western Himalayas became prized acquisitions for collections in the U.S. and Europe. Western explorers, scholars and travelers removed these works — often surreptitiously — from their places of origin. Today many of these works reside in public and private collections.

“With these exhibitions, we are raising questions that a university museum is uniquely capable of addressing — specifically, the complex issues surrounding the origins of an object and how its meaning can shift with context. Through a dynamic schedule of free public programs, we will present audiences with unique opportunities to consider and examine these questions,” Corrin said.

Complementing the exhibitions are scholarly lectures and movie screenings (see calendar) that are directly relevant or intended to transport museum goers into the Himalayan ambience at least in imagination. There are talks on border crossing as a way of life, early Kashmiri art, development of Tibetan Buddhism, and the textile trade; movies on Mount Everest, Shangri-La, a Himalayan convent, war-torn Srinagar, its Dal Lake and Afghan archeology.

An illustrated color catalogue is available for sale that shares new research and perspectives developed while forming the exhibition.

Photo captions (in order of priority): The exhibition “Collecting Paradise: Buddhist Art of Kashmir and Its Legacies” showing at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University, Evanston, runs through April 19 and is free to the public.

1) Crowned Buddha Shakyamuni. Kashmir or northern Pakistan; eighth century Brass with inlays of copper, silver and zinc Asia Society, Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection of Asian Art, 1979.044.

2) Thangka of Four-Armed Mahākāla. Western Tibet, Tholing Monastery (?); 15th century Pigments on cotton Solomon Family Collection.

3) A Pair of Female Attendants. Kashmir; Eighth century Ivory Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund, 1972.35.1 and 1972.35.2.

“Exhibition on Kashmir Buddhism Unveils Complex Legacy of Himalayan Art” (DTC Jan. 16, p.???)

When Lisa Corrin took over as director of Northwestern University’s Block Museum of Art in February 2012, one of the proposals on the table concerned a small study show focused on the little-known art of Kashmir. Corrin was so taken with the idea that she decided to considerably enlarge the scope of the undertaking, turning it into not the biggest but what she is calling the most ambitious exhibition in the museum’s history. [.] In addition, it is the first Block exhibition to tour in eight years. The show is traveling to the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City, an institution focused on the art of the Himalayas that provided significant loans to the offering and shared some of the costs.

>

Until the mid-19th century, Kashmir referred to the valley between the Himalayan and Pir Panjal mountain ranges. It was once a powerful autonomous Hindu and Buddhist region, especially in the 8th and 9th centuries, when it exerted significant religious and cultural influence on Central Asia, especially the nearby Western Himalayas.

When Kashmir came under Muslim rule in the 14th century, much of the region’s Buddhist art and even some of its artists were transferred tothe Western Himalayas, which continued to emulate and build on Kashmiri artistic styles for several subsequent centuries.

One facet of this exhibition is to simply showcase the complementary Buddhist objects from these two regions, which are sometimes included in larger exhibitions of Asian art but rarely are spotlighted on their own. “The objects, I have to say, are just dynamite pieces,” said Robert Linrothe, an associate professor of art history at Northwestern University. “They sustain any kind of looking, whether it’s aesthetic, religious or historical. They’re really quite impressive objects.“

Linrothe, who is serving as the curator for this exhibition, has made more than 20 trips to the Western Himalayas and is one of the world’s leading experts on the Buddhist art of this area.

In addition, he wants in this show and a subsidiary one, “Collecting Culture: Himalaya through the Lens,” to tell a larger story of collecting: Both how pilgrims and others from the Western Himalayas collected and preserved the art of Kashmir but also a second, more pernicious tale of how Western collectors subsequently acquired the art.

“So, the title of the exhibition, ‘Collecting Paradise,’ is in a double sense,” Linrothe said.

According to him, Western collectors sometimes bullied and corrupted monks in the Western Himalayas into selling – often at night – what for Buddhists are consecrated objects, and many of these pieces later found their way into museum collections.

“I’m certainly not saying that any of these have been stolen,” Linrothe said, “This is not a sensationalist kind of [assertion that] ‘These should be returned’ or anything like that. It’s just that they [these acquisitions] are kind of slippery, and they’re the kind of thing that is generally not looked at in the light of day.”

Kyle MacMillan, “Block Museum Shines Spotlight on Kashmir Art in New Exhibit” (Chicago Sun-Times, 12 Jan 2015)

Source: WHN Media Network