But no matter how much the RSS connection with Godse’s act of assassination may have been disproven, Gandhi’s murder has been a millstone around the neck of the Hindu movement and especially the RSS. – Dr Koenraad Elst

But no matter how much the RSS connection with Godse’s act of assassination may have been disproven, Gandhi’s murder has been a millstone around the neck of the Hindu movement and especially the RSS. – Dr Koenraad Elst

The ideological helplessness of the contemporary Hindu nationalists comes out immediately when you question them about Mahatma Gandhi. The assessment of Gandhi’s significance for Hindu society and the fact of his murder by a Hindu are embarrassing topics for them, which the opponents of the Hindu movement are still exploiting to the hilt.

Invariably, the so-called secularists seemed to regard the RSS (with its parivar or “family” of affiliated organisations including the BJP) as the “alleged murderers of the Mahatma”. As Craig Baxter, in The Jana Sangh, has remarked, this allegation is in defiance of the judicial verdict in the Mahatma murder trial: “The RSS and the Jana Sangh do, however, frequently face accusations of being the ‘murderers of Gandhi’. These most commonly come from the Congress ‘left’ or from the Communists, are used as political slogans, and, of course, show a disregard for the legal decision in the case.”

But no matter how much the RSS connection with Godse’s act may have been disproven, in The Jana Sangh, Baxter notices that Gandhi’s murder has been “a millstone around the neck” of the political Hindu movement and especially the RSS.

Faced with this allegation, sticky though disproven, two attitudes are possible: continuing in a defensive position by issuing denials whenever the allegation is uttered, or taking it in one’s stride and even defiantly accepting it. It is believed that the latter was generally the rhetorical tactic of Bal Thackeray, leader of the national-populist Shiv Sena. Thus, when the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, was ascribed to Shiv Sena volunteers, Thackeray declared, as The Times of India reported, “If Shiv Sainiks did it, I am proud of them.” On the Gandhi murder too, he had taken a defiant stand, even though he never accepted that the assassination could be attributed to the Shiv Sena in any way. In 1992, he shocked the opinion-makers by declaring that future generations would erect statues for Godse rather than for the Mahatma.

The RSS family’s line has been just the opposite: they have exhausted themselves in denials and condemnations of the murder. Because of their enemies’ persistence, this has meant that in this respect, as in many others, the RSS family has been continually on the defensive. In fact, seeing the RSS on the defensive has obviously fuelled their opponents’ gusto in using this allegation. The RSS leaders keep on repeating that the RSS had been officially cleared of all charges of complicity, but to no avail: the media in India and abroad just keep on associating them with the murder of the Mahatma.

To prove its innocence, the RSS family has invested a lot of words in denouncing the murder and praising the Mahatma. Immediately after the murder, the RSS supremo Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar called it a “heinous crime” and directed all branches to suspend normal routine for the thirteen days of Hindu mourning “out of respect and sense of sorrow at the tragic demise of Mahatmaji.” Years later, he still gave speeches in praise of the Mahatma, just like any average Congressman. In this case, however, no outsider was willing to credit him with sincerity, perhaps wrongly.

The Godse brothers’ testimony on the RSS

Here is Nathuram Godse’s own version of his involvement with the RSS:

I have worked for several years in RSS and subsequently joined the HMS [Hindu Mahasabha] and volunteered myself as a soldier under its pan-Hindu flag.

About the year 1932 late Dr Hedgewar of Nagpur founded the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangha in Maharashtra also. His oration greatly impressed me and I joined the Sangha as a volunteer thereof. I am one of those volunteers of Maharashtra who joined the Sangha in its initial stage. I also worked for a few years on the intellectual side in the Province of Maharashtra. Having worked for the uplift of the Hindus, I felt it necessary to take part in the political activities of the country for the protection of the just rights of the Hindus. I, therefore, left the Sangha and joined the Hindu Mahasabha.

However, Nathuram Godse’s straightforward declaration has lately been challenged by none other than his brother and accomplice Gopal. On the occasion of the annual Nathuram Godse memorial meeting (Mumbai, November 17, 1993), Gopal was interviewed and said, against the umpteenth statement by Hindu nationalist leader L. K. Advani disowning Nathuram, that Nathuram had been a baudhik karyavah (“intellectual officer”, ie, the above-mentioned “work on the intellectual side”), an RSS worker of some rank at least at the local level. The four Godse brothers had been groomed by the RSS at the initiative of the eldest, Nathuram. Though their locus of activity shifted somewhat, there never was a clean break with the RSS.

It is true that their guru, Veer Savarkar, had spoken with mild contempt of the RSS, a well-known fact which gave credibility to Godse’s court statement that he had left the RSS at about the time of Savarkar’s accession to the presidency of the HMS in December 1937. But then, Savarkar had no personal connection with the RSS, while the Godse brothers had spent time in RSS meetings in their young days and developed a close link with it, not so easy to disown. Therefore, Nathuram contrived to create the impression that the RSS had little to do with him, simply to avoid creating more trouble for the RSS in the difficult post-assassination months. Gopal explains that Nathuram did not leave the RSS, he only stated so because Golwalkar and the RSS were already in a lot of trouble after Gandhi’s murder.

There is really no controversy here. Nathuram Godse never rejected the RSS, but he was not functioning within the RSS structure in the years before the murder. He had chosen to do political work whereas the RSS scrupulously stayed out of party politics. Ideologically, he still was an RSS man. That is why he sang the nationalist RSS song Namaste sada vatsale matribhume (“I bow to thee, loving Motherland, always”), a fixed part of every RSS shaakhaa (branch) meeting when he walked to the gallows.

It remains true, moreover, that the RSS had professed a very negative opinion of the Mahatma’s failed policy of “Hindu-Muslim unity”, an opinion which was also Nathuram Godse’s motive for the murder. Much of Godse’s speech consisted of comments which Hindu activists of any affiliation, including the RSS, had been making ever since the Mahatma’s involvement in the pan-Islamist Khilafat Movement of 1920–21 (discussed below). There is just no denying that while the murder was the handiwork of a small group of conspirators, their motive had been an indignation over Gandhi’s policies which they shared with the entire Hindu Mahasabha, with the RSS and with many common Hindus and Sikhs besides.

However, being of the same political opinion does not constitute complicity in the crime. When a great man is murdered, you always see vultures descend on the great opportunities for political exploitation which the concomitant quantity of guilt and blame offers. When Yitzhak Rabin was murdered in 1995, many in the Israeli Labour Party blamed the opposition Likud bloc, alleging that with its virulent anti-Rabin propaganda, it had “created the right climate” for the murder. Likewise, after Mahatma Gandhi had criticized Swami Shraddhananda’s work of reconverting Indian Muslims to Hinduism, a Muslim killed the Swami; and so, Nathuram Godse alleged that Gandhi had “created the right climate” for the murder, or words to that effect: he provoked a Muslim youth to murder the Swami. But we need not emulate Godse in his conflation of criticism and murder, do we?

The RSS may rightly disown the responsibility for Godse’s act. It never believed in assassination as a method of conducting politics. Before and after 1948, the RSS has been involved in many a street fight, but never in targeted assassinations of public figures. Even during Godse’s trial, no evidence was ever produced that the organisation had ordered or condoned Godse’s initiative to murder the Mahatma.

If not for moral reasons, then at least out of self-interest, the RSS was most certainly disinclined to associate itself with a crime of this magnitude. After all, the negative consequences that actually followed were perfectly foreseeable. And yet, the RSS ought to publicly (as most of its sympathizers do privately) own up at least Godse’s argumentation, for that was the view of Gandhi’s policies commonly held by the RSS activists in the 1940s.

Inspired by Savrakar

In paragraphs 26–47, Nathuram Godse details the story of his involvement in the Hindu Sanghatan movement (“self-organization”, of which the HMS and the RSS were instances) and his political relation with Veer Savarkar:

I have worked for several years in RSS and subsequently joined the Hindu Mahasabha and volunteered myself to fight as a soldier under its pan-Hindu flag. About this time Veer Savarkar was elected to the presidentship of the Hindu Mahasabha. The Hindu movement got verily electrified and vivified as never before, under his magnetic lead and whirlwind propaganda. Millions of Hindu Sanghatanists looked up to him as the chosen hero, as the ablest and most faithful advocate of the Hindu cause. I too was one of them. I worked devotedly to carry on the Mahasabha activities and hence came to be personally acquainted with Savarkarji.

And that, to Godse, is all there is to say about their personal relationship.

Godse explains how Savakar encouraged and financially supported Apte and him when on March 28, 1944, they started their Marathi daily Agrani (forerunner, vanguard). This paper was closed down in 1946 by the authorities for flouting the ban on clear and factual reporting on communal violence (ie, detailing the genesis of the riots and the community-wise breakdown of the victim numbers), but immediately restarted under the name, Hindu Rashtra. Though they sometimes met at the HMS office in Bombay, Savarkar never involved himself in Godse’s enterprise, not even to contribute a regular column as Godse had requested him to do. As Partition came near, Godse lost his faith in the HMS’s ability to stem the tide and keep India united:

1934: Some three years ago, Veer Savarkar’s health got seriously impaired and since then he was generally confined to bed. … Thus deprived of his virile leadership and magnetic influence, the activities and influence of the Hindu Mahasabha too got crippled and when Dr Mookerji became its President, the Mahasabha was actually reduced to the position of a hand-maid to the Congress. It became quite incapable of counteracting the dangerous anti-Hindu activities of Gandhiite cabal on the one hand and the Muslim League on the other. … I determined to organise a youthful band of Hindu Sanghatanists and adopt a fighting programme both against the Congress and the League without consulting any of those prominent but old leaders of the Mahasabha.

The “youthful band” was the Hindu Raksha Dal (“Hindu Protection Squad”) with a membership never exceeding 150. Godse was now his own man directing his own political activities, independent of the RSS and HMS. Whatever their ideological kinship, they cannot be held responsible for Godse’s act.

Disappointed with Savarkar

Let us now look in more detail into the organisational estrangement between Godse and his mentor Savarkar. Of the events “which painfully opened my eyes about this time to the fact that Veer Savarkar and other old leaders of the Mahasabha could no longer be relied upon” (para 35–44), Godse mentions the following examples. In 1946, Savarkar went out of his way to personally reprimand Godse when Apte and he had heckled Gandhiji during a prayer meeting in a Hindu temple in Bhangi Colony (Delhi), where Gandhiji had read passages from the Quran in spite of protests by the Hindu worshippers, and where he had spoken in defence of Bengal chief minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the man possibly politically (and probably also directly) responsible for anti-Hindu pogroms in Calcutta and Noakhali. Godse quotes Savarkar:

… Just as I condemn the Congressites for breaking up your party meetings and election booths by disorderly conduct, I ought to condemn any such undemocratic conduct on the part of Hindu Sanghatanists also.

Of greater political importance was the fact that Savarkar and the other HMS leaders recognised the post-partition state of India, hoisted its flag, and accepted Nehru’s invitation that their party president, S. P. Mookerjee, join the provisional government:

… To my mind to recognise a state of divided India was tantamount to being a party to the cursed vivisection of India. … Veer Savarkar went further and actually insisted that the tri-colour flag with the wheel should be recognised as a National Flag.

… In addition to that, when Dr Mookerji asked his permission through a trunk call to Veer Savarkar as to whether Dr Mookerji should accept a portfolio in the Indian Union Ministry, Veer Savarkar emphatically replied that the new Government must be recognised as a National Government whatever may be the party leading it, and must be supported by all patriots….

By inviting the HMS president into his Cabinet, Nehru effectively neutralised the HMS. In the opposition, the party could have been a dangerous adversary, especially as the champion of the Indian unity which Congress had betrayed; but as a partner in the government, and one with little influence at that, it became harmless. In terms of political strategy, Godse’s critique of the HMS leadership’s cooperationist line was probably correct. On the other hand, one should concede to Nehru a certain genuine generosity and a fitting sense that the first native Government should be a truly national one, with representatives of all political tendencies. Then again, it is also true that Dr Mookerjee and Dr Ambedkar had been invited by him on advice from Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Patel; Nehru himself was rather reluctant at that time and felt increasingly uncomfortable with them subsequently, as events went to prove.

Savarkar, the veteran fighter for independence, was apparently too happy with the long-awaited sovereignty as embodied in the first native Union government to think in terms of party politics. But Godse did not believe that a truly sovereign and representative government was compatible with the intrusive presence of Gandhiji:

… I myself could not be opposed to a common front of patriots, but while the Congress government continued to be so sheepishly under the thumb of Gandhiji and while Gandhiji could thrust his anti-Hindu fads on that Congressite government by resorting to such a cheap trick as threatening a fast, it was clear to me that any common front under such circumstances was bound to be another form of setting up Gandhiji’s dictatorship and consequently a betrayal of Hindudom.

If even Savarkar and Mookerjee were willing to surrender to Gandhiji’s dictates, Godse judged that the time had come for a new and independent political activism:

Every one of these steps taken by Veer Savarkar was so deeply resented by me that I myself along with Mr Apte and some of the young Hindu Sanghatanist friends decided once and for all to chalk and work out our active programme quite independently of the Mahasabha or its old veteran leaders. We resolved not to confide any of our new plans to any of them including Savarkar.

Here, Godse denies once more that Savarkar had played a role in the assassination. Approver Digamber Badge kept on making this very allegation, possibly because he or the investigating police officers expected some reward from Pandit Nehru in exchange for catching such a big fish. HMS leader and Godse’s lawyer L. B. Bhopatkar revealed several years later, in Manohar Malgonkar’s The Men Who Killed Gandhi (a volume published by the Savarkar Memorial Committee on February 16, 1989), that Dr Ambedkar, the Law Minister in Nehru’s Cabinet at that time, met him secretly to inform him that Nehru was personally interested in involving Savarkar, though there was no evidence to prove Savarkar’s complicity.

His mere imprisonment was successful enough in eliminating him from politics. Manohar Malgonkar, in The Men Who Killed Gandhi writes “The strain of the trial, and the year spent in prison while it lasted, wrecked Savarkar’s health and finished him as a force in India’s politics.”

At any rate, the prosecutor could not produce the slightest evidence connecting Savarkar with the murder. In August 1974, Badge admitted to an interviewer that his testimony against Savarkar had been false. Ever since, journalists reluctant to give up the polemical advantage of connecting the main Hindutva ideologue with the murder, glibly introduce him as “a co-accused in the Mahatma murder trial.” In Nehruvian “secularism”, the superficiality of thought is compensated for by thoroughness in dishonesty.

A rumour about Godse and Savarkar

At this point, we cannot altogether ignore a rumour which frequently appears in the secondary literature on Hindutva. According to Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, the writers of the overrated book Freedom at Midnight, the most widely-read introduction to the history of India’s attainment of independence, including the Mahatma murder story, Godse had had a homosexual relation with Savarkar.

As usually happens with rumours, this one too has spread. Thus, in M. J. Akbar’s Nehru biography, the claim becomes a curt statement of fact: “Nathuram Godse, thirty-seven, homosexual, fanatic, ascetic, …” Akbar’s book has been republished as a Penguin paperback, available in the whole world. Similarly, the French edition of Freedom at Midnight claims that Savarkar was a homosexual and frequent opium user, even though few people knew about it. And of Godse, that before he chose to remain a celibate, “he had had, so it is believed, only one sexual experience, with his political mentor Veer Savarkar, as initiator.”

In his psychological comment on the relation between Gandhi and Godse, well-known psychologist Ashis Nandy registers Collins’ and Lapierre’s claim and expresses serious doubts about it, but also mentions those very facts that seem to make it plausible to Freudians.

Firstly, as a child, Godse had been treated like a girl by his parents, in the hope of magically warding off the fate of their three earlier sons, who had all died in infancy. Nathuram literally means “Nose-ring Ram” (his given name was Ramachandra or Ram for short), because he had been made to wear this feminine ornament.

Secondly, Savarkar, who spent a decade in the Andaman penal colony, must have been familiar with aberrant sexual practices common in prisons; the Pathan camp guards had a grisly reputation in this regard. These conjectures don’t prove anything, but they provide the infrastructure of plausibility on which rumour-mongers build their inferences.

Fact is that serious reporters on the Gandhi murder trial mention nothing of the kind and that the claimed source of the rumour, Nathuram Godse’s brother Gopal, strongly denies (to Nandy as well as to myself) ever having told any such thing to Collins and Lapierre. According to him, the authors had meanwhile given an undertaking to his lawyer that the passage would be deleted from future editions of the book. The newer Indian prints have indeed left out the offending passages. The burden of proof definitely lies with those who persist in repeating the rumour, and until they discharge it, we must hold them guilty of slander.

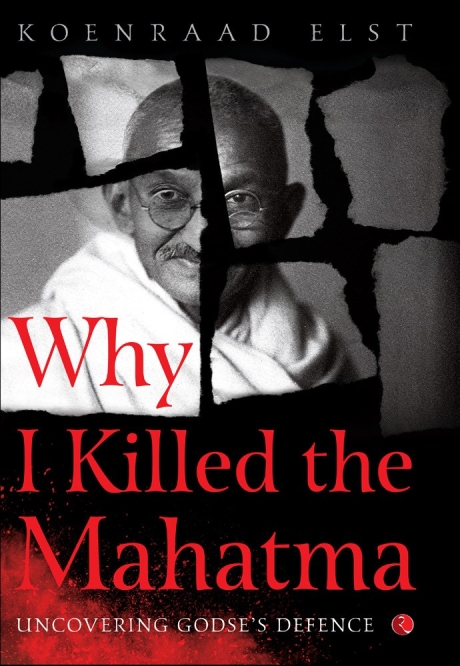

Having disposed of this alleged intimate relationship, we are left with the more relevant and undisputed fact that Godse was a devoted political follower of Savarkar. Godse joined the HMS just around the time when Savarkar, an acclaimed hero of the independence struggle, became its president (December 1937). For Godse, this was the latest step in a career as an activist for the Hindu cause, which included years of active membership of the RSS (which can be inferred to cover the period 1932–37). But to outsiders, the truly surprising and ironical fact must certainly be that Godse had started his involvement in politics as a Gandhian activist. — Excerpted from Why I Killed the Mahatma, Rupa Publications, New Delhi. This excerpt copied from Daily-O, 30 January 2018.

» Dr Koenraad Elst is an author, historian, and orientalist in Belgium.

Source: https://bharatabharati.wordpress.com/2018/02/02/nathuram-godses-ties-with-the-rss-koenraad-elst/