New Delhi: The Indian government’s National Sanskrit Institute, whose headquarters are in a run-down section of western New Delhi, has the hallmarks of a long-neglected state project.

New Delhi: The Indian government’s National Sanskrit Institute, whose headquarters are in a run-down section of western New Delhi, has the hallmarks of a long-neglected state project.

Unattached electrical wires dangle down its facade, and one of its senior scholars, Ramakant Pandey, greeted a recent visitor in a fluorescent-lighted office, his mouth stained red with paan, the Hindi word for the betel leaf mixture chewed throughout Asia.

It felt like an office that did not receive many visitors. Still, Pandey was not downhearted.

“Good times are coming,” he said.

This summer signals a changing of the guard, as a new group of elites led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi set themselves up in government-issued bungalows in the capital, displacing the Anglophone intelligentsia clustered around the Indian National Congress.

It is unclear what this means for the fabric of high society in New Delhi, with its golf links and polo tournaments. But one project almost certain to benefit is the teaching of Sanskrit, the ancient language of the Brahmin scholars, an effort that has been ignored by the Congress and promoted by the Hindu right wing.

“This government will help Sanskrit, we know that,” Pandey said. “They are traditional people – they love literature, they love culture.”

“And Modi-ji is a traditional prime minister,” he added, using a Hindi honorific.

Many linguists view these efforts skeptically, noting that even in Sanskrit’s heyday, about 1,500 years ago, it was primarily used by Brahmin intellectuals as a language of scholarly discourse and never served as a mother tongue. In the most recent census, only 50,000 Indians described Sanskrit as their first language – more than the 14,000 that gave that answer in 2001, but still less than 0.01 percent of the population of an estimated 1.2 billion people.

This has not quenched the enthusiasm of Hindu nationalists, who see the language as a link to an ancient, homegrown civilization swept away by Persian-speaking Muslim emperors and English-speaking British viceroys. Early independence leaders had hoped to phase out English as an official language, but that provoked widespread protests in the country’s south, where Hindi is not widely spoken.

To this day, bursts of resistance to English percolate though Hindu-right circles. Last summer, the Bharatiya Janata Party leader, Rajnath Singh, was quoted as saying that English “had caused a great loss to the country,” and that “there are hardly any people who speak Sanskrit now.”

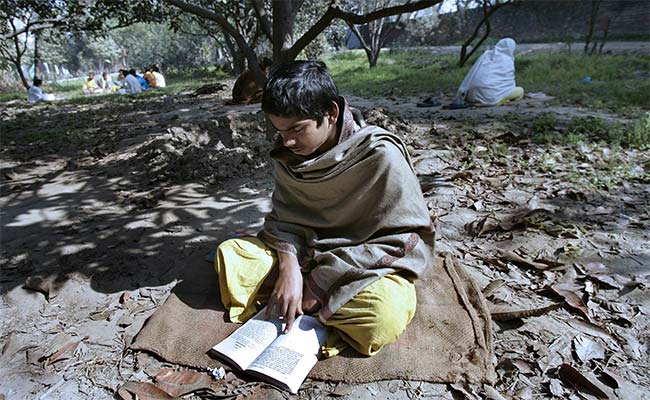

Revivalists have taken some unusual steps in an attempt to bring Sanskrit into daily usage, like raising their children in Sanskrit-only households and using the scholarly language in pop-culture genres.

This movement emerged again early this month, when newly elected members of Parliament were taking their oath of office. The foreign minister took her oath in Sanskrit, followed by at least two dozen others. Modi himself sometimes prefers to avoid speaking English despite his proficiency, addressing foreign leaders in Hindi in the presence of a translator. In late May, there had been rumors that he would go a step further and take his oath of office in Sanskrit.

Rakesh Kumar Misra, who edits a weekly Sanskrit newspaper in New Delhi, said that in the days before the ceremony, he had prepared a full draft of Modi’s oath to be published on the occasion.

But in the end, Misra said, Modi stuck with Hindi.

“It would have been a great boost for Sanskrit,” Misra said. “He must have decided that it was more important to bind everyone together.”