The Journey of Caribbean Hindus

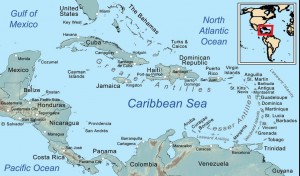

The abolition of the slave trade created a labor shortage that threatened the survival of the Caribbean plantation economy, particularly in the larger European colonies like Trinidad and Guyana. Africans were not willing to subject themselves voluntarily to the oppressive conditions of life on the plantations, and experiments with workers from Madeira and China were unsuccessful. India proved to be the most reliable source of willing laborers with the required skills. It provided a steady stream of immigrants from 1838, the year the first group of 396 Indians arrived in Guyana, until 1917 when indentured Indian immigration was finally abolished. By that time, 238,909 Indians had migrated to Guyana and 143,939 to Trinidad. Most of them came from districts in the North Indian states of Bihar and the United Province. A significant proportion of these immigrants chose to return to India after completing the terms of their contracts. Seventy-one percent of those who made the arduous journey around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Atlantic chose to make their homes in the Caribbean. Their choice is the reason for our presence in New York City today.

Along with their physical skills and knowledge of sugar cultivation, Hindu immigrants introduced to the Caribbean the essential elements of one of the world’s most ancient, culturally rich and philosophically sophisticated cultures. The insights and achievements of India found expression in the songs, dances, myths, stories and religious texts transported in the memories and meager belongings of the immigrants. Immigrants to the Caribbean, and specifically immigrants to Guyana, were the first to sow in the soil of the western world the seeds of Hindu consciousness and way of life that had evolved in Asia. Fifty-five years before Swami Vivekananda spoke at the Parliament of World Religions in 1893 in Chicago, Hinduism was being practiced in the Caribbean.

This remarkable story of the survival of the Hindu tradition remains to be narrated properly. It is the story of religious survival in the midst of abject poverty and no official support for their religious and cultural wellbeing. The broader community viewed them with suspicious and schizophrenic eyes. While they were required for their physical skills on the sugar plantations, their beliefs, ceremonies of worship, life-cycle rituals and sacred narratives were denounced as superstitious and unenlightened. The reasons for the perception and treatment of Hindu religion and culture as inferior and backward are many. The principal reason will be found in the fact that the dominant values of the Caribbean were those of western Christian Europe. Those who judged Hinduism by these values proclaimed it to be different and inferior.

They were correct about the fact that the Hindu traditions are different, but wrong in denouncing it as inferior because of being different. There are several important ways in which Hindu traditions differed from dominant religion of Christianity.

In contrast to most forms of Christianity, which are very exclusive in their understanding of revelation and salvation, the Hindu tradition understood revelation in pluralistic ways. Hinduism affirms the oneness of the divine, but does not limit divine revelation to one historical moment or person. It portrays the one divine in many forms and describes it with many names.

While introducing new sacred texts to the Caribbean, like the Vedas and the Ramayana, Hindu immigrants also brought with them ancient murti or iconographic representations of God. The use of these in rituals and festivals brought forth charges of idolatry and polytheism from a Christian-influenced culture that was hostile to the imaging of the divine in material forms.

In addition, the understanding of God as immanent in all things led to a reverence for nature that was wrongly perceived as pantheistic. All of these contrasts were accentuated further by differences in language, dress, and diet. In the midst of hostility and pressures to convert, the Hindu tradition endured and, in many cases, even flourished.

The Journey to America

In the mid-1960’s Hindus from the Caribbean, embarked on another significant historical journey. Driven by political fears and economic uncertainties Hindus, especially from Guyana, migrated in significant numbers to North America. It is story of migration with empty pockets, long years of separation from family, relentless efforts to gain an education and untold hours of hard work. These Hindus from the Caribbean are among the first to construct places of Hindu worship and to establish the tradition on the soil of the United States and Canada.

The migration of Hindus from the Caribbean to North America brought new challenges and some old ones persisted. Many of these challenges are shared with Hindus whose roots are in other parts of the world, including India, Africa, Fiji, Mauritius and Afghanistan.

Three challenges for Hindus in America

Being a Religious Minority

While the number of Hindus in North America has been increasing, Hindus still constitute a small percentage of the total population of the United States and Canada. The preservation and transmission of religious values become increasingly difficult when these have to be done in a context where the norms of the dominant culture are different and in some instances in conflict with Hindu ideals. Our children are exposed to a variety of religious and cultural choices. Minorities wrestle, more than others, with issues of identity and carry a greater burden of self-explanation. The children of minorities often seek the acceptance and approval of the majority community and, for this reason, may be more willing to accept the values of this community, even when these contradict their own. Americans still know very little about Hinduism and many of the predominant images are negative.

The separation of religion and culture in America

Our historical context is also unique for another important reason. Historically, Hinduism has embraced both religion and culture and the disentanglement of one from the other is quite difficult. It is significant that there is no Sanskrit equivalent for the word, “religion,” and the term, dharma, which is sometimes equated with “religion”, is far more inclusive. The detachment of religion and culture, however, is rapidly becoming a reality in the experience of a new generation of Hindus born in the western world. The unity of religion and culture is being severed and the traditionally pervasive influence of Hinduism is relegated to fewer areas of life. Musical tastes, cuisine, recreational activities, and dress are increasingly influenced by sources outside of the Hindu tradition. This separation of religion and culture, presents us with challenges and questions. How will the Hindu tradition develop and thrive in a context in which it does not exert a pervasive cultural influence? What forms will it assume and what would it mean to be a Hindu? Will it be limited to ritualistic practices in the home and temple? What will be its public character, if any? This problem of the separation of religion and culture was less acute in the Caribbean.

Religious Transmission

The growing separation between religion and culture highlights a third feature and challenge of our new context. The unity of religion and culture, to which I have already referred, minimized the need for special agencies for the transmission of the tradition. It was correctly assumed that a child would receive the necessary religious exposure by the mere fact of growing up in a particular community where Hindu traditions were embedded in the culture. When I was a child attending an Arya Samaj primary school, we used to recite a series of questions and answers about Hinduism from a small text. One of the questions was, “Why are you a Hindu?” and the answer following was, “Because I was born a Hindu.” It may have been a good answer in that time, but I am not sure that it will work for a new generation today. For the first time, increasing numbers of Hindus will be Hindus by choice and will have to be reconverted or converted to Hinduism.

Ten needs of Hindus in America

Hindu unity

One of the imperatives for confronting our contemporary challenges is Hindu unity. Religious divisions that would hardly cause a ripple in a population of 800 million in India become major fractures when that population is a minority. There is an urgent need for a coming to together of the different traditions of Hinduism to reflect on and to affirm the common aspects of our Hindu heritage. This unity about which I speak is not one that requires the overlooking or elimination of differences of doctrine and practice that exist among us. Hindu unity, however, will certainly enable us to better utilize our limited resources and speak with a common voice on matters of shared concern.

The traditional feud between Sanatanists and Arya Samajists has taken its toll on Caribbean Hinduism. Hindu unity requires that these two traditions (sampradayas) be in dialogue with each other. It is sad that Hindus often find it easier to engage in dialogue with persons of other faiths than with fellow Hindus. Certainly our Arya Samaj brothers and sisters can appreciate the positive nature of many post-Vedic developments in Hinduism and the profound theology of grace that underlies the use of murtis (icons) in puja (worship). At the same time, Sanatanist Hindus can see Swami Dayananda Saraswati as one of the great reformers of our tradition who renewed the significance of the Vedas and sought to rejuvenate Hinduism. 19th century issues should not continue to divide us today, but a generosity of heart on both sides is necessary along with a renewed emphasis on what we share.

Greater focus on jñana (wisdom)

We must have a deeper focus on and appreciation for the wisdom or jñana dimension of our tradition. It is accurate to say that in the transmission of the tradition the emphasis, historically, has been on orthopraxis, with a focus on ritual worship. In the western world, however, Hindus are increasingly challenged to articulate and transmit their tradition in a manner that places more emphasis on its fundamental teachings. If we desire young Hindus to commit themselves to this tradition, we will have to convince them of its worth by a reasonable explanation of its teachings in relation to other competing views.

Hindu teachers

The number of dedicated Hindu educators are too few.

Traditionally, Hinduism distinguished between the function of the ritual specialist and the religious teacher or educator. The ritual specialist is the purohita or pujari who officiated in home and temple rituals and whose training consisted primarily in the recitation of mantras and the performance of ritual. The pujari did not function as a teacher.

Rambachan leading a Diwali (Festival of Lights” service. Photo illustration by A Journey through NYC religions/Khant Khant Kyaw

The guru or acharya is the teacher of wisdom. These teachers were, in many cases, though not all, monks (sannyasins) and their training was entirely different. They were trained in the authoritative Hindu texts such as the Upanishads and the Bhagavadgita.

During the migration of Hindus from India to the Caribbean, many purohitas came, but few acharyas. Caribbean purohitashave done a remarkable job in developing the skills to be both ritual specialists and teachers and deserve much commendation. In many cases such skills were developed through individual initiative; in others cases by discipleship and study with a guru. The field of human knowledge, however, has grown and the wisdom and skills required to be an effective Hindu teacher are more than anyone can develop on his or her own initiative or through study with a single teacher. The Hindu teachers and educators who are needed today must be well-versed, not only in the traditions of Hinduism but also in the major trends of contemporary intellectual discourse in the various branches of human knowledge so that they could provide coherent, rational and articulate interpretations of Hinduism, We will need to work to establish institutions and design curricula where such training is afforded to students with the proper religious and intellectual aptitudes.

An expanded temple role

The new context and challenges require an expanded role for the traditional Hindu temple. The traditional Hindu temple is primarily a place of worship where the sacred murti is housed. We visit our temples for darshana (to see the murti), and to offer ritual worship (puja). Preserving this central purpose, our temples must increasingly become centers of teaching and learning about the Hindu tradition, ensuring the successful transmission of the tradition from one generation to another.

Since we cannot guarantee that a Hindu child will be Hindu by the fact of birth alone, temples must become the centers where age appropriate teaching is conducted. This is already happening in many temples and resources must be shared. The temple as a center of teaching must now complement the temple as a center of worship. Caribbean Hindus have strengthened the congregational forms of temple worship and these forms continue to serve the community well.

Strengthening Hindu families

An emphasis on an expanded role for the Hindu temples must not be at the expense of the practice of Hinduism in our homes. The vital and living center of Hinduism, throughout its history, is the home and family. It is in the family that one’s identity as a Hindu is formed and one understands first what it means to be Hindu.

If we wish our children to learn about the Hindu tradition, we must take the initiative to become learners ourselves. Your own desire and effort to learn will ignite and inspire their own. Above all else, our lives must embody the finest values of our tradition. We will not make a lasting impact on our children unless our actions, public and private, are infused with the core values such as daya (compassion), truth (satya), generosity (dana), and self-control (dama). In the matter of religion, children learn from what we do; not what we say. A child’s faith is undermined by adult religious hypocrisy.

Overcoming the privatization of Hinduism

We must ensure, as Hindus, that we do not treat our religious teachings and values as private. Privatization implies compartmentalization. Such a compartmentalization of human life may lead to fundamental and problematic contradictions in human conduct. Let us say, for example, that compassion and generosity are central values of our religion; privatizing these values means that their practice is limited to temple or home. Surely, this will not be in keeping with the spirit of our tradition since we do not find any instructions in our sacred texts asking us to limit compassion and generosity only to these spheres. These values are meant to influence all aspects of our lives.

The privatization of religion leads also to its increasing irrelevance. If our traditions cannot guide us in our helping us to make decisions and choices about the significant issues of our times, our tradition will grow in irrelevance. It means that the sphere of influence of our tradition will be extremely limited and narrow.

This is a particularly important issue for us as Hindus in the United States and in the Western world. The major national debates in which religion is involved are conducted largely without Hindu voices. If we wish to be participants in these significant discussions, we must begin by clarifying our own positions on these issues and then finding the appropriate spaces to ensure that Hindu voices contribute to these debates. This is one important way also of ensuring the transmission of the Hindu tradition to a new generation. We transmit our religious tradition to our children by teaching them our ways of worshipping and praying. We transmit our tradition also by teaching them how to draw from the deep wisdom and insights of the Hindu tradition in making decisions and formulating their own worldviews. In this way, the Hindu tradition becomes more meaningfully embodied in their lives.

It is important for us to understand that the Hindu tradition has never been only about the attainment of moksha. Certainly moksha is the highest goal of human existence (parama purushartha). The Hindu tradition is also centrally concerned with our lives in the world and with right living (sadachara). This is the realm of dharma and thedharma literature is vast and extensive. Dharma is concerned with right living in the world. It requires a clarification about the core values of the tradition. We need to apply Hindu values and analysis to all matters of human concern, including politics and economics.

A Hindu outreach to the larger community

Hinduism continues, for many reasons, to be a deeply misunderstood religion in the United States. In a survey of American attitudes about Hindus, over 600 persons, two-thirds of those surveyed, had no knowledge of Hindu beliefs and practices. Most associated Hinduism with “cow worship,” “many gods and temples,” and “India.”

I mention this reality to make the point that Hindu temples, in addition to our primary obligations to the Hindu community, must also reach out to the larger community in order to ensure that there is accurate and sympathetic understanding of Hinduism.

Humility and self-criticism

One of the great values of our tradition is vinaya or humility. The Bhagavadgita commends the person who is rich in learning (vidya) and humility. Humility is the recognition that, as human beings, we are limited in knowledge and in the practice of virtue. There is always more to know and always room for growth in the development of a virtuous character.

Humility is not possible without the willingness to be self-critical. It is the recognition that in the past and present, we have not always lived up to highest ideals of our tradition. We can be oppressive and unjust, dishonest and uncharitable as individuals and as a religious community. Even the best among us, as the Bhagavadgita reminds us, can fall.

Right commitment

Our commitment to the Hindu tradition must be for the right reasons. Many young persons are turning away from religion because religion seems so much to be associated with violence and hatred. Almost every major conflict in the world today has an intrareligious or interreligious element. Our commitment to the Hindu tradition does not require us to hate or stereotype persons of other faiths, ethnicity or cultures. Our Hindu identity must be positive, not negative.

Remembering the central teaching of the Hindu tradition

My final suggestion is the necessity for us all to remember what, for me, is the central and core teaching of our tradition and to guided in all aspects of our lives by this. This teaching is articulated repeatedly in the Vedas, the Bhagavadgita and Ramayana. In Bhagavadgita (13:27), Bhagavan Krishna describes true seeing as knowing God to exist equally in all beings (samam sarvesu bhutesu tisthantam paramesvaram). He reiterates this in the final chapter (18:61), reminding Arjuna that God exists in the heart of all beings (ishvara sarvabhutanam hrddeshe’rjuna tisthati). In the Ramayana of Tulasidas, Lakshmana ask Shri Rama to explain the meaning of wisdom (jnana). Rama answered in five simple words: dekha brahma saman sab mahi (to see God in all beings).

To value a boy over a girl, to exploit children, to abuse women, to mistreat the elderly, to discriminate against the disabled are all expressions of blindness to this truth. This is the teaching that draws us into lives of compassion and service of others and which led Swami Vivekananda to declare that “they alone live who live for others.”

——————————————————–

Anantanand Rambachan is professor of religion at St. Olaf College, Minnesota. This article is taken from his keynote address to the Hindu Caribbean Conference of America in New York on October 6, 2012. He is the author ofThe Advaita Worldview: God, World and Humanity, The Hindu Vision, Gitamrtam: The Essential Teachings of the Bhagavadgita and A Hindu Theology of Liberation (forthcoming). He is a member of the Theological Education Steering Committee of the American Academy of Religion, a member of the International Advisory Council for theTony Blair Faith Foundation, and a member with Consultation on Population and Ethics, a non-governmental organization, affiliated with the United Nations. Twice, he delivered the invocation address at White House’s celebration of the Hindu festival of Diwali.